Fermi level

The Fermi level is a hypothetical level of potential energy for an electron inside a crystalline solid. Occupying such a level would give an electron (in the fields of all its neighboring nuclei) a potential energy  equal to its chemical potential

equal to its chemical potential  (average diffusion energy per electron) as they both appear in the Fermi-Dirac distribution function,[1]

(average diffusion energy per electron) as they both appear in the Fermi-Dirac distribution function,[1]

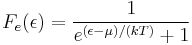

which calculates the probability that an electron with energy  occupies a particular single-particle state within such a solid. T is the absolute temperature and k is Boltzmann's constant. When

occupies a particular single-particle state within such a solid. T is the absolute temperature and k is Boltzmann's constant. When  the exponential equals 1, and the value of

the exponential equals 1, and the value of  describes the Fermi level as a state with 50% chance of being occupied by an electron for the given temperature of the solid.

describes the Fermi level as a state with 50% chance of being occupied by an electron for the given temperature of the solid.

Detailed explanations and applications

The Fermi Dirac distribution function

The Fermi-Dirac distribution f(E) gives the probability that a single-particle state of energy E would be occupied by an electron (at thermodynamic equilibrium):

where:

- μ is the parameter called the chemical potential (which, in general, is a function of

);

);  is the electron energy measured relative to the chemical potential;

is the electron energy measured relative to the chemical potential; is Boltzmann's constant;

is Boltzmann's constant;- T is the temperature.

In particular,  .

.

Conduction band referencing and the parameter ζ

If the symbol ℰ is used to denote electron energy level measured relative to the bottom of the conduction band, then in general we have ℰ = E – EC, and in particular we can define Sommerfeld's parameter ζ [2] by ζ = EF - EC. It follows that the Fermi-Dirac distribution function can also be written

The band theory of metals was initially developed by Sommerfeld, from 1927 onwards, who paid great attention to the underlying thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. He describes ζ as the "free enthalpy of an electron", but this name is not now in common use. ζ is called here the "conduction-band referenced Fermi level", although in the literature of metal physics it is just called "Fermi level". ζ is in general a function of temperature, and the value at zero temperature is widely known as the Fermi energy, sometimes written ζ0. In the special case of a noninteracting Fermi gas (or "jellium"), the temperature dependence is:

In other situations, such as a doped semiconductor, the temperature dependence can be very complicated, and depends on the detailed doping and density of states.[3]

The idea of conduction-band referencing, and the associated parameters ζ0 and ζ, are useful when concentrating on the properties of electrons in a metal body that is electrically neutral, is electrically isolated from the rest of the world, and has no long-range electrical fields inside it. This is the situation often considered in basic metal physics. For more information see the article on Fermi energy.

One can think in terms of adding electrons one by one to a positively-charged "container", taking the Pauli exclusion principle into account. ζ0 is the energy level, at zero temperature, at which the body under analysis becomes electrically neutral. In this context ζ0 is sometimes called the "charge neutrality level". ζ0 can also be interpreted as the energy (relative to the base of the conduction band) of the last electron added before the metal becomes electrically neutral.

Earth-based referencing and the parameter µ

Alternatively, if the symbol H is used to denote electron energy level measured relative to the Fermi level of the Earth, then in general we have H = E – EG, and a quantity µ can be defined by µ= EF - EG, where (as above) EG denotes the Fermi level of the Earth. It follows that the Fermi-Dirac distribution function can also be written in the form:

![f(H) = \frac{1}{1 %2B \mathrm{exp}[(H-\mu)/k_{\mathrm{B}} T]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/77fa92c40fd8449903930ea7d90ee828.png) .

.

This quantity μ is called here the "(Earth-referenced) electrochemical potential", or alternatively the "Earth-referenced Fermi level" – although in the literature is it often just called "Fermi level".

The quantity "electrochemical potential" relates closely to the chemical quantity "partial molar energy". In the present context, the electrochemical potential can be regarded as the work that would be needed to add an electron at the Fermi level of the body (or part of a body) under analysis. In ordinary chemistry one has to specify or assume by convention the "standard state" in which an added entity existed before being added. Thus, when defining electrochemical potential, there is a logical need to specify where the electron comes from (so that the work – in particular the electrical work – needed to transfer it can be calculated correctly). In the present context, the electron is considered to come from the Fermi level of the Earth. This is the most sensible choice of reference state, though not the only conceivable one – see below.)

Specifically, one can define the (Earth-referenced) electrochemical potential μA of a body "A" as the work needed to transfer an electron from the Fermi level of the Earth to the Fermi level of body "A".

This concept of "electrochemical potential" is needed in situations where different parts of a larger system are each separately in (approximate) local thermodynamic equilibrium, but are not in electrical equilibrium with each other. In this case the electrochemical potentials of the different system parts will not be equal. This implies a tendency for electrons to move from the location of higher electrochemical potential (higher Fermi level) to the location of lower electrochemical potential (lower Fermi level). As long as there is nothing equivalent to a battery in the system, the transfer of charge will lead to the creation of an electrostatic field that will make the electrochemical potentials (Fermi levels) become equal. Electrical equilibrium corresponds to the situation where the electrochemical potentials (Fermi levels) have become equal.

The distinction between ζ and µ

The need to distinguish physically between the parameters ζ and µ can be clearly seen by considering the case of a body "A" that has a good electrical connection to Earth, but is sufficiently well insulated thermally from the Earth that it can be in (approximate) local thermodynamic equilibrium at a temperature different from that of the Earth. Consider what happens when the temperature of body "A" changes, but that of the Earth does not. The electrochemical potential (Earth-referenced Fermi level) µA of body "A" is unchanged (at value 0), because it remains locked to that of the Earth. However, the conduction-band referenced Fermi level ζA of body "A" does change, in accordance with the formula above. Thus, what happens physically is that the energy level of the bottom of the conduction band of body "A" (and, hence, the whole band structure of body "A") moves up in energy, relative to the Fermi level of the Earth, as the temperature of body "A" increases. There is also some charge transfer between body "A" and the Earth, which is needed in order to keep μA = 0.

Obviously, in discussions of this kind, the existing nomenclature arrangements (whereby the same name "Fermi level" may be applied to both ζ and µ) do not help overall clarity of discussion.

"Fermi level" in semiconductor physics

In semiconductor physics it is conventional to work mainly with unreferenced energy symbols. This is possible because the relevant formulas of semiconductor physics mostly contain differences in energy levels, for example (EC-EF). Thus, for developing the basic theory of semiconductors there is little merit in introducing an absolute energy reference zero. This can be qualitatively understood as asserting the importance of the encountered potential difference instead of the absolute potential difference.

The central task of basic semiconductor physics is to establish formulas for the position of the Fermi level EF relative to the energy levels EC and EV (the level of the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band), taking into account the effects of "doping". Doping introduces additional electron energy levels into the band gap, that may or may not be populated by electrons, dependent on circumstances and temperature, and causes the Fermi level EF to shift from the energy level (relative to the band structure) that it would have had in the absence of doping. This energy level that the Fermi level has in the absence of doping is called the intrinsic Fermi level (or "intrinsic level") and is usually denoted by the symbol Ei.

The theory of semiconductor physics is constructed in such a fashion that – in a situation of complete thermodynamic equilibrium – the position of the Fermi level, relative to the band structure, determines both the density of electrons and the density of holes.

If a semi-conducting body "B" is electrically connected to Earth, in circumstances where there is no battery or equivalent in the system, then the Fermi level of body "B" is locked to the Fermi level of the Earth. In these circumstances, changes in doping in the semiconductor cause shifts in energy of the whole band structure of body "B", relative to the common Fermi level of the Earth and body "B". In these circumstances doping (or changes in doping) also causes some transfer of charge between body "B" and the Earth.

For further information about the Fermi levels of semiconductors, see (for example) Sze. [4]

Local thermodynamic equilibrium and the concepts of "quasi-Fermi level" and "imref"

Both with metals and with semiconductors, it is necessary to consider how to modify the theory when these materials form part of an electrical circuit through which a steady electric current is flowing. This is done by assuming that approximate thermodynamic equilibrium can exist "locally", and that a corresponding "local Fermi level" can be defined. This "local Fermi level" varies with position, and is sometimes called the "quasi-Fermi level" (QFL).

In some situations, such as the junctions between different materials (or differently doped regions of a single material) that occur with diodes and transistors, there can be a "jump" in quasi-Fermi level across the junction. It is often impossible to satisfactorily define the concept of quasi-Fermi level close to the junction, because the populations of electrons and/or holes are not even in approximate thermodynamic equilibrium there.

Close to a junction of this kind it is possible for populations of electrons and holes to be separately in approximate local thermodynamic equilibrium, but for these populations not to be in thermodynamic equilibrium with each other. In such circumstances the quasi-Fermi levels for the electrons and holes will be at different levels relative to the band-structure. In such circumstances a quasi-Fermi level has sometimes been called an imref (Fermi spelled backwards), but the term "quasi-Fermi level" seems to be replacing this name.

The relation between local Fermi level (local electrochemical potential) and voltage

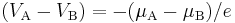

There is a close relationship between the local electrochemical potential for electrons and the quantity called "voltage" in the analysis of electric circuits, denoted here by V. The difference (VA-VB) in voltage between two points "A" and "B" in an electrical circuit is related to the corresponding difference (µA-µB) in electrochemical potential by the formula

,

,

where e is the elementary positive charge, as earlier. This formula should be considered as the fundamental definition of the term "voltage difference" (note that the phrase "voltage difference between" is very commonly shortened to "voltage between").

If one needs to allocate a numerical value to "voltage", rather than "voltage difference", then a reference zero must be defined. The most useful system of referencing takes body "B" as the Earth, and sets µB=0 and VB=0. In circuit analysis this is achieved by attaching a "Ground" symbol to some appropriate point of the circuit.

In this context, it must be clearly understood that the term "voltage difference" always relates to differences in electrochemical potential that occur inside conductors. The term "voltage difference" should never be used to refer to differences in electrostatic potential, whether these occur inside electrical conductors or in space outside them (even though such differences are also normally measured in volts).

To avoid possible confusions between electrostatic potential energy and electrochemical potential, it is better for analysis of electric circuits to use the less ambiguous term "voltage difference", rather than the more ambiguous term "potential difference" or its abbreviation "P.D."

In practice, differences in voltage between different points of an electric circuit (and, hence, differences in the electrochemical potential for electrons between these points) can be measured by using an (ideal) voltmeter. Real instruments can be made that approximate well to ideal voltmeters.

Electrochemical potential and its components

The quantity "electrochemical potential" is a form of thermodynamic potential. Despite its name, in the present discussion it is a quantity with the dimensions of energy. In some contexts (such as the definition of local work function) it is possible and useful to think of the electrochemical potential as composed of two components – an "electrostatic component" and an "internal chemical component" (also variously called a "chemical component", a "purely chemical component", a "bulk component", an "exchange-and-correlation component" or a "correlation-and-exchange component").

There is, however, no method of measuring these components separately. Thus, some scientists take the view that the overall quantity, here called the "electrochemical potential", should simply be called the "chemical potential". This article takes the view that the terms should be regarded as synonymous, but that the name "electrochemical potential" is less likely to be misunderstood.

Why it is not advisable to use "the energy at infinity" as a reference zero

In principle, one might consider using, as a reference zero for electrochemical potential, the situation of a stationary electron at rest at infinity (or, at any rate, at rest at a large distance from a specified body). This approach is not advisable, because the work needed to place such an electron at the Fermi level of the body depends on the detailed arrangement of the atoms at the surfaces of the body. A body with its atoms configured so that all of its faces have one type of crystallographic orientation with one particular value of local work function will have a value of electrochemical potential different from that of the same body when its atoms are configured so that all of its faces have a different type of crystallographic orientation with a different particular value of local work function. Thus, attempts to define electrochemical potential in this way cannot lead to the kind of universal parameter that thermodynamics ideally requires.

The parameter that gives the best approximation to universality is the "Earth-referenced electrochemical potential" used earlier. This also has the advantage that it can be measured with a voltmeter.

Other terminology problems

- Chemical potential and Electrochemical potential: In some parts of the literature the term "chemical potential" is used instead of "electrochemical potential". In the past there has been no consensus as to whether these two terms should mean the same thing. Some textbooks continue to make a distinction (and, worse, there are alternative conventions as to what each term means). The more modern view is that "chemical potential" should mean the same thing as "electrochemical potential", – but that in some contexts there is a separate concept – called here the "internal chemical potential" – that is the energy left when the "purely electrostatic component of electrochemical potential" is subtracted out. (In other contexts it may not be possible make a division into components in any sensible way.) In any case, it is usually only the total combined thermodynamic potential that can be measured. As already noted, it is thought less confusing here to use the name "electrochemical potential" for the total combined thermodynamic potential.

- Alternative uses of the name "Fermi energy". It is normal in solid-state physics to use the term "Fermi energy" as a name for ζ0, as done here.[5] However, particularly in semiconductor physics and engineering, the term "Fermi energy" is sometimes used as a synonym for "Fermi level".[6]

Some other complications

- Charging effects. In cases where the "charging effects" due to a single electron are non-negligible, the above definition does not quite work. For example, consider an capacitor made of two identical parallel-plates. If the capacitor is uncharged, the Fermi level is the same on both sides, so one might think that it should take no energy to move an electron from one plate to the other. But when the electron has been moved, the capacitor has become (slightly) charged, so this does take a slight amount of energy. In a normal capacitor, this is negligible, but in a nano-scale capacitor it can be more important. This can be dealt with, for example, by saying that the Fermi level is N times the energy required to move 1/Nth of an energy to the reference level (where N is a very large number), or by saying that the Fermi level is the energy required to move an electron to the reference level, not counting the energy stored in electrostatic fields.

- Non-equilibrium effects. In many cases, the occupancy of electronic states is not described by the Fermi-Dirac distribution, because the electron distribution is not in local thermodynamic equilibrium. For example, when light is shining on a semiconductor, there is no value of the Fermi-Dirac distribution function f(E) that describes the actual occupancy of electronic states. (The light shifts electrons to more energetic levels in a characteristic way.) In such cases, there is no Fermi level. Sometimes, the occupancy of conduction-band states can be described by putting the Fermi level in a certain position relative to the band structure, whereas the occupancy of valence-band states can be described putting the Fermi level in a different position relative to the band structure. In this case, the two different Fermi levels are called quasi-Fermi levels, as in the case described earlier. In other situations, such as immediately after a high-energy laser pulse, one cannot even define quasi-Fermi levels; the electrons and holes are simply said to be "non-thermalized".

- Fermi level equilibration. Any material or device in thermodynamic equilibrium will have a constant Fermi level everywhere in the device. Neither the electrostatic potential energy nor the internal chemical potential on their own need to be constant in the device, but the Fermi level (their sum) does. For example, in an equilibrium p-n junction, the electrostatic potential energy is higher on the n-type side than the p-type side (this is associated with the so-called "built-in field"), but this is precisely offset by the equal-and-opposite change in internal chemical potential.

The Fermi level can vary (or not exist at all) in any non-equilibrium situation, such as:

- Under an applied voltage,

- Under illumination from a light-source with a different temperature, such as the sun (this allows for photovoltaics),

- When the temperature is not constant within the device (this allows for thermocouples, for example),

- When the device has been altered, but has not had enough time to re-equilibrate (this allows for pyroelectricity, for example).

Summary

In summary, the name "Fermi level" is used in science in several different (but related) ways.

The name is sometimes simply used as a "label" for the energy level of the one-electron state for which the occupation probability (according to the Fermi-Dirac distribution function f ) is 0.5. This usage has been called here "unreferenced". All of the symbols used here for Fermi level can be used in this way. The convention in this article has been that the symbol E (and variants of it with specific subscripts) can only be used in this unreferenced way.

Alternatively, the name "Fermi level" can be used as the name of a quantity (ζ or μ) that has a well-defined numerical value because it is defined as measured relative to a specified energy reference zero. in this article, the symbol ζ is used when the reference zero is the bottom of the conduction band, as in metal physics. The symbol μ is used when the reference zero is the Fermi level of the Earth, as in the analysis of electrical circuits. In this article, ζ is called the "conduction-band referenced Fermi level"; μ is called the "Earth referenced Fermi level" or the "(Earth-referenced) electrochemical potential". The value ζ0 that ζ takes at zero temperature is widely known as the "Fermi energy".

Confusion arises because there is no accepted international nomenclature for the three different logical entities called "Fermi level", and because in each of the main contexts in which one of these entities is used it is often just called "Fermi level".

Further confusion is generated when the term "Fermi energy" is misused as a name for any entity other than ζ0, and by the existence of a variety of different interpretations of the pair of names "chemical potential" and "electrochemical potential". As already indicated, the approach of this article is that these are alternative (synonymous) names for μ, but that the name "electrochemical potential" is less likely to be misunderstood.

A possibility of confusion also arises when the symbol μ and/or the name electrochemical potential (or chemical potential) is used for the entity denoted here by ζ. It seems unlikely that ζ as used here can meaningfully be regarded as an electrochemical potential, because of obvious difficulties in giving a real-world specification of the "standard state" in which the electron existed before it was added to the body under analysis.

Footnotes and references

- ^ Kittel, Charles; Herbert Kroemer (1980-01-15). Thermal Physics (2nd Edition). W. H. Freeman. p. 357. ISBN 978-0716710882. http://books.google.com/books?id=c0R79nyOoNMC&pg=PA357.

- ^ Sommerfeld, Arnold (1964). Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics. Academic Press.

- ^ Balkanski and Wallis (2000-09-01). Semiconductor Physics and Applications. ISBN 9780198517405. http://books.google.com/books?id=lmg13dHPKg8C&pg=PA113.

- ^ Sze, S. M. (1964). Physics of Semiconductor Devices. Wiley. ISBN 0471056618.

- ^ See, for example, Ashcroft and Mermin. Solid State Physics. ISBN 0030493463.

- ^ For example: D. Chattopadhyay (2006). Electronics (fundamentals And Applications). ISBN 9788122417807. http://books.google.com/books?id=n0rf9_2ckeYC&pg=PA49. and Balkanski and Wallis (2000-09-01). Semiconductor Physics and Applications. ISBN 9780198517405. http://books.google.com/books?id=lmg13dHPKg8C&pg=PA113.

![f(E) = \frac{1}{1 %2B \mathrm{exp}[\frac{E-\mu}{k_\mathrm{B} T}]} = \frac{1}{1 %2B \mathrm{exp}[\frac{\epsilon}{k_\mathrm{B} T}]}~,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f42441775c029eddd94dd4dc63d847b8.png)

![f(\mathcal{E}) = \frac{1}{1 %2B \mathrm{exp}[(\mathcal{E}-\zeta)/k_{\mathrm{B}} T]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/92cd191eb06688d1ab58bc485dcd2bb7.png)

![\zeta = \zeta_0 \left[ 1- \frac{\pi ^2}{12} \left(\frac{k_{\mathrm{B}} T}{\zeta_0}\right) ^2 - \frac{\pi^4}{80} \left(\frac{k_{\mathrm{B}} T}{\zeta_0}\right)^4 %2B \cdots \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7d9ee1e7a4f7d8acbb4142f5657cd18b.png)